How can economists and policy-makers take the environment into consideration?

Independent correspondent, Zoha Shawoo, discusses whether cost-benefit analysis can work in favour of the environment, and how the price assigned during the process may not necessarily reflect the true value to those affected.

As global consumption in the forms of fossil-fuel burning, deforestation for agriculture and water overuse have been increasing exponentially over the last few decades, the turn of the century has been characterised with an increased focus towards ‘sustainability’. Sustainable development was famously defined as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet our own needs’ in the Brutland report of 1987, entitled ‘Our Common Future’. This was the first report to suggest a physical limit on the exploitation of the natural environment, leading to several policies such as the 1992 Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit, the 2002 Johannesburg summit and, more recently, the 2012 Rio + 20 UN Conference on Sustainable Development. These policies intended to influence a sustainable approach that would reach the maximum balance between economic growth, social progress and environmental stewardship. However, in order to put such a theory into action, a method was needed that would allow economists and policy-makers to take the environment into consideration when making decisions, thus leading to the development of the Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) of the environment. [1]

The purpose of a cost-benefit analysis is to determine whether or not a policy or project should be undertaken by weighing the benefits of the project against its costs. This is done in purely monetary terms, with a monetary value attached to all factors and variables for and against the project. A positive resulting balance would usually allow the policy to be proceeded with. However, what makes a sustainable approach differ from a conventional CBA is that environmental values and environmental attributes are also assigned monetary terms, allowing them to influence the outcome of the CBA. This can be explored through a particular example in Tanzania, which also reveals the drawbacks of the CBA.[2]

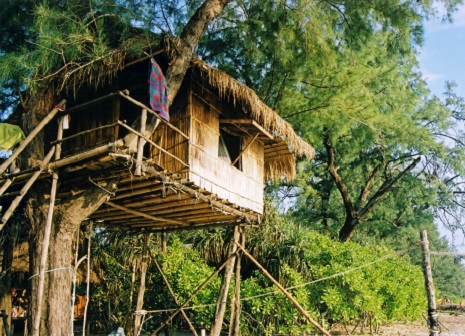

In Tanzania, the issue of trading off one thing for another through the CBA comes up when considering whether or not a certain area of forest should be conserved or converted into cropland. If conserved, the benefits would entail the monetary units of the resulting ecotourism, water regulation by the forest, carbon sequestration by the trees (which would minimise contribution to climate change), non-wood products that the forest would provide, species biodiversity and the spiritual or cultural values of the forest that are important to many of the local villagers. Alternatively, conversion of the forest to cropland would result in the monetary benefits of timber revenues and crop revenues to both companies and local farmers that depend on farming for their livelihoods. However, both scenarios also have their monetary drawbacks. In the case of conservation, there would be forest management costs, especially if it is opened to tourism, as well as the cost of compensation to farmers who would be losing their livelihoods. Similarly, conversion would entail the costs in terms of carbon emissions as it would no longer be sequestrated, as well as labour and farming costs. All these values were included in monetary terms when the cost-benefit analysis was carried out, and the result was the conservation of the forest being more beneficial than its conversion into cropland.

It is important to note that the CBA should not be blindly relied upon and has several drawbacks, one of the primary ones being that the vast value of nature cannot be captured in monetary terms. Many goods and benefits from the environment do not have a market value, such as those of biodiversity and water regulation; these are known as ‘ecosystem services’. However, in order to take them into account when it comes to policy-making, a monetary value has to be assigned. This could be in terms of, for example, how much it would cost to replace a certain service. However, it is very important to note that ‘price’ is not the equivalent of ‘value’. For instance, in the above example, the conservation of the forest would mean that poor farmers would no longer have wood as a fuel. Thus, when compensation is paid, it will be the equivalent of the price of that firewood. However, it is very unlikely that, with this compensation, farmers will be able to pay for alternative fuels; although the ‘price’ of the product is equivalent to the compensation, the ‘value’ is not. A similar problem arises when you try to assign monetary values to the spiritual, cultural or religious benefits of nature to local communities, which can be very difficult to quantify. Furthermore, nature is regarded as so vast and as having so many benefits that it is impossible to assign values to everything nature comprises of. In fact, there are also ethical objections against including such aspects of nature in the CBA at all as it involves ‘putting a price on nature’. [3]

One overall flaw of the cost-benefit analysis is that it cannot capture the livelihoods of local communities as well as their dependence on nature accurately in monetary terms. However, does this mean that such variables shouldn’t be taken in to account when carrying out the CBA at all? Or it is better to have at least some representation of such aspects of nature? To conclude, the cost-benefit analysis is effective in at least taking the environment into consideration when carrying out policies. However, it cannot be wholly relied upon as it cannot capture the complexity of the relationship of populations with the environment. [4]

Thank you for taking the time to read this article, as ever we appreciate and value your opinions. This article reflects the opinion of the author only. If you have any comments or feedback, drop us a line at [email protected].

[1] Baker, S. (2006) Sustainable Development. Routledge, London.

[2] Pearce et al. (2006) Cost-benefit analysis and the environment – Recent developments.

[3] Turner et al. (2010) Ecosystem valuation: A sequential decision support system and quality assessment issues. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1185: 79–101.

[4] Martinet, V. (2012) Economic Theory and Sustainable Development.